Netflix & Nollywood

Nollywood has gone from video cassettes to Netflix and is now looking to build a global audience.

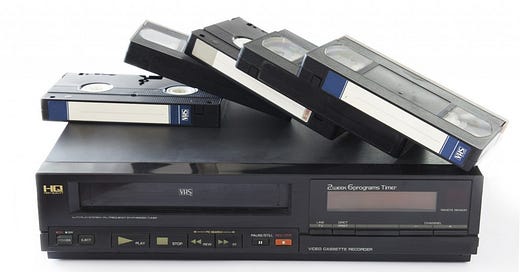

If you had a truckload of blank VHS tapes in 1989 Lagos, what would you have done with them?

This was the question Kenneth Nnebue, an electronics trader regularly in business with the Chinese importers of old tech into Africa, had to contend with.

This was a time when TV and VCR (Video Cassette Recorder) combo was just becoming more commonplace in Nigerian homes. They had one thing going for them: easy access to video content and intuitive design, all you had to do was pop in a tape and press play.

Kenneth loved movies. He constantly watched whatever foreign titles he could grab on his VCR, growing a large library of cassettes, as they were fondly called at the time. It was one day while watching one of his favourite movies (nobody knows which one it was) that he had his eureka moment. He figured he could record movies onto the blank cassettes and sell them. Simple as that.

He quickly hatched a plan for his new idea. He was going to finance and produce the films himself. He already had the equipment so he resolved to use camcorders to record these movies straight to his blank cassettes.

The only people in Nigeria producing and recording video films at the time were artists from the"Alarinjo"; the traditional Yoruba travelling theatre. They distributed their films by screening them using video projectors. Kenneth was going to take a different approach with his blank cassettes.

He started off his filmmaking project by financing a couple of low budget titles. Mostly shooting them with a single VHS camcorder and two video recorders. His budget? $200, about N2,000 (at that time) on each movie. The first of these films would be in Yoruba.

Then in 1992 , he struck gold with the Igbo title Living in Bondage.

The film was, to put it mildly, a hit. However, he barely made any profit as pirated copies of the movie were distributed far and wide. Nonetheless, Kenneth knew a winner when he saw one. So he doubled down on the movie’s success and made a sequel.

This time he used a bigger budget. For distributing this sequel, he used a network of local Nigerian traders. He also launched an aggressive marketing campaign powered by posters and banners. The sequel was also a hit and this time around, he bagged a handsome profit.

Living in bondage VHS tape in a full-colour paper cover. Image by OperaNews

Kenneth went on to make Glamour Girls. The first Nigerian video film in English. Living in Bondage and Glamour Girls are recognised as the beginning of Nollywood.

Today, a modern rendition of Kenneth’s Living in Bondage can be found among the handful of Nigerian movies on Netflix.

The Nollywood Paradox

Some people think that Nollywood movies largely lack the detail and precision that bigger counterparts like Hollywood have. They believe Nollywood plots are poor, that the production quality is incredibly low. Yet, Nollywood continues to grow in reach and audience.

Often criticised for doing a poor job of establishing Nigerian pop-culture identity. Somehow the “Nigerianess” of Nollywood’s content is understood and loved by a lot of Nigerians, Africans and those who genuinely engage with the culture globally.

While Nigerian music has always made the world sit up and listen, it’s been felt that the movie industry was too far behind, taking too much time to sort itself out, let alone catch up.

Today, Nigeria’s film industry is the biggest narrator of African tradition and pop culture. Churning out over 2500 movies per year.

The second-largest producer of movies in the world is no stranger to criticism or ridicule.

Old vs New

After Nigeria gained independence in 1960, it managed to put together a fragile film industry that struggled to get any traction until Kenneth came along with his blank cassettes. This forged the foundation of Nollywood 1.0. Commonly called Old Nollywood.

Old Nollywood was focused on themes like comedy, social ethics, melodramatic domestic conflicts, village life, urban modernity, religion, and of course, the supernatural.

As Old Nollywood grew in relevance and revenue, it became more technically inclined. Featuring more films that revolved more around affluence and sophistication. Old Nollywood then transitioned into new Nollywood. Nollywood 2.0.

Where Old Nollywood focused on releasing as much content as possible. New Nollywood did its best to focus on quality content. Nigeria’s film industry now wanted more than local relevance, it aspired for global relevance.

New Nollywood cannot be divorced from the influence of its predecessor. The internet, especially social media, is replete with memes from Old Nollywood. These memes don’t just inspire the exploration of Nigeria’s history, they also convey the everyday experiences of Nigerians and some other Africans.

PayTV and The Streaming Wave

Videotapes dominated the Nigerian movie industry from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Then DVDs/VCDs and PayTv (DSTV) came along and everything changed.

Pirated DVDs/VCDs of Nollywood movies could be found on street corners, in traffic and rental video shops. Even the African diasporan population and the Caribbean population was hooked to this Nollywood DVD craze.

In 2003, DSTV (Multichoice Nigeria) launched a dedicated channel for Nollywood movies called the Africa Magic channel. Over the next few years, it went on to launch three more channels individually dedicated to showing Nigerian films in Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo. The films were licensed from Nigerian filmmakers who were very happy with a chance to rake in more revenue. A welcome solace for them as they continued to battle piracy.

Nollywood’s DVD/VCD model still continued to thrive because DSTV decoders had not penetrated the Nigerian market just yet, and consumers still enjoyed the convenience DVDs provided. They could buy them for around $2 (N300) and watch movies at their own time.

In 2010, a 29-year young entrepreneur in Southeast London noticed that his mother had moved on from the British soap operas she used to watch religiously. Mrs Njoku now watched Nollywood movies and had quite the stash of DVDs/VCDs just like a lot of other people back home in Nigeria.

Mrs Njoku’s son realised the potential these movies his mother loved so much had. And that became the seed for his new venture. He was going to put Nollywood on the internet, literally.

Jason Njoku came back to Nigeria and began negotiating distribution deals with film producers. He wanted to put up Nollywood movies on his newly created Youtube Channel NollywoodLove. The channel went viral. Getting a million views from over 170 countries.

Sometime in April 2014, Jason ditched his Youtube channel and announced the launch of video-on-demand streaming platform IROKO. IROKO was called the “Netflix of Africa” especially as the popular streaming giant was not available on the African continent yet.

IROKO set out to increase global access and distribution for Nollywood and other movie industries in Africa. It became the largest global distributor of African films. With most of the films from Nollywood. By 2016 other Video-On-Demand companies like TRACE Play, Ibakatv, SceneOne and Netflix (finally) could count themselves as IROKO’s competitors in Africa.

A Netflix powered Nollywood

Netflix acquiring Lionheart, its first original Nigerian film, coupled with the success of The Wedding Party, Nollywood’s highest-ever grossing movie, signalled an impending Nigerian film industry boom.

It became more obvious when more Nollywood movies began to pop up on Netflix. When the company announced a deal with John Boyega to produce non-English western and eastern African films, and another announcement of a similar deal with Mo Abudu to create new Nigerian originals, it was a confirmation of the Nollywood’s potential. This Netflix foray into producing its own Nollywood content is a very big win for the industry. Access to capital, increased revenue streams and even bigger recognition means the bar can be raised even higher. It is not a magic wand wave just yet though.

The backing from Netflix doesn’t automatically make Nollywood a more dominant industry. There is still some progress to be made regarding intellectual property and copyright laws. The same can be said about regulatory restrictions as well as issues with policies put forward by the government body that regulates content in Nigeria.

A Nollywood global dominance will remain a dream as long as content laws and policies fail to be market-friendly. So there must be concerted efforts to attract even more foreign investment. More funds for Nollywood means more new global markets to exploit. It also means a well-intentioned nudge for filmmakers to explore a wider range of themes that capture the essence of the average Nigerian.

Nollywood’s Future

Nollywood’s journey to acquiring a global audience is filled with hurdles. Not only of capital and distribution channels but of language conformity.

These movies are filled with narratives that stem from different ethnicities. Each providing its own distinct backdrop for themes that revolve around Nigeria. The global digitisation of movies has caused tension for Nollywood filmmakers. A tension between making movies searchable (mobile) and the loss of ethnic languages and accents.

One notable example is Jenifa, Funke Akindele’s critically-acclaimed movie. It may be a movie rife with Yoruba accents, but its digital versions do not retain these accents that made it so popular. This tension was also revealed when Netflix’s first original Nigerian film, Lionheart, got disqualified from the Academy’s Best International Film category for being “too English”. This for a film many regard as very Igbo and Nigerian.

While we strive for a more digital inclusive world and in tandem learn about its limits. We must also understand at a ground level how the current digital world affects particular cultures and groups. Especially content creators.

Nollywood filmmakers must strive to truly represent Nigerian culture in the best possible way to a global audience. They must understand the benefits and drawbacks of language in Nigerian cinema. The attention from Netflix certainly seems like the next step in this process.

Things we’ve kept a tab on

Biometric identification: African’s next frontier Market?

According to a World Bank estimate, Africa alone accounts for half of the 1.1 billion people in the world unable to prove their identity, making it a major potential market for companies in the sector.

The African market for biometric and digital identity documents alone is estimated at €1.4 billion by the specialist firm Acuity Market Intelligence. On a global scale, the mobile biometric recognition segment (using smartphones and tablets, particularly for payments) is set to become the driving force in this market, with global turnover expected to rise from €18 billion in 2018 to €44.7 billion in 2022.

Governing the Mini-Grid Electricity Delivery Model in Nigeria

Globally, there are more than 1.3 billion people (20 per cent of the world’s population) without access to modern and affordable energy sources to meet their domestic and commercial needs. The majority of these people are in the rural areas of developing or least-developed countries. Of the 1.3 billion people, 1.1 billion are without access to modern electricity supply. Access to modern energy sources has been shown to have a direct correlation on the human development index and, it is an enabler for alleviating poverty, social progress, gender equality and environmental resilience within the rural areas of developing countries.

Africa is looking to be next Animation Global Hotspot

The winner of Cartoon Network Africa's Creative Lab competition, Ridwan Moshood from Nigeria, has opened an animation production company called Pure Garbage, to produce a series of his award-winning original property, Garbage Boy & Trashcan, in anticipation of a global distribution deal. The studio is a partnership between Moshood, US-based producers Baboon Animation, and the African Animation Network (AAN), a for-profit social enterprise that’s instigating and coordinating the development of animation capacity across the continent.

The vanishing textiles of Africa

A look at some of the fashion collections created of authentic African textiles now owned by Makena Mwiraria of Ari Africa, with the intention of saving some of them in an existing museum space or building a special museum for this purpose, with African Heritage House as a potential site. Here is a textile tour through the African continent.

How a flurry of newsroom revolts has transformed the American press

A piece on how groups of reporters and staffers are demanding the firing or reprimand of colleagues who’d made politically “problematic” editorial or social media decisions.

For all our infamous failings, journalists once had some toughness to them. We were supposed to be willing to go to jail for sources we might not even like, and fly off to war zones or disaster areas without question when editors asked. It was also once considered a virtue to flout the disapproval of colleagues to fight for stories we believed in (Watergate, for instance).

Can you trade up a bobby pin till you get a house? Check out this video of how a TikToker is going about it.

If you enjoyed this tabbing installment, you should absolutely subscribe and share it with at least a hundred of your friends (or slightly more than that).